Political conservatives generally believe that there are features in culture that should be conserved or restored. So, conservatives value preservation of those features or a return to them.

Political liberals focus on the mistakes and the evil found in the past, so they value progress, change, and “moving forward”.

Conservatives generally see wisdom in the past. They study it and emulate it in most ways.

Liberals of today will sometimes see little or nothing of value or virtue in the past of its own culture.

In this regard, I am a conservative. I resonate with GK Chesterton when he said,

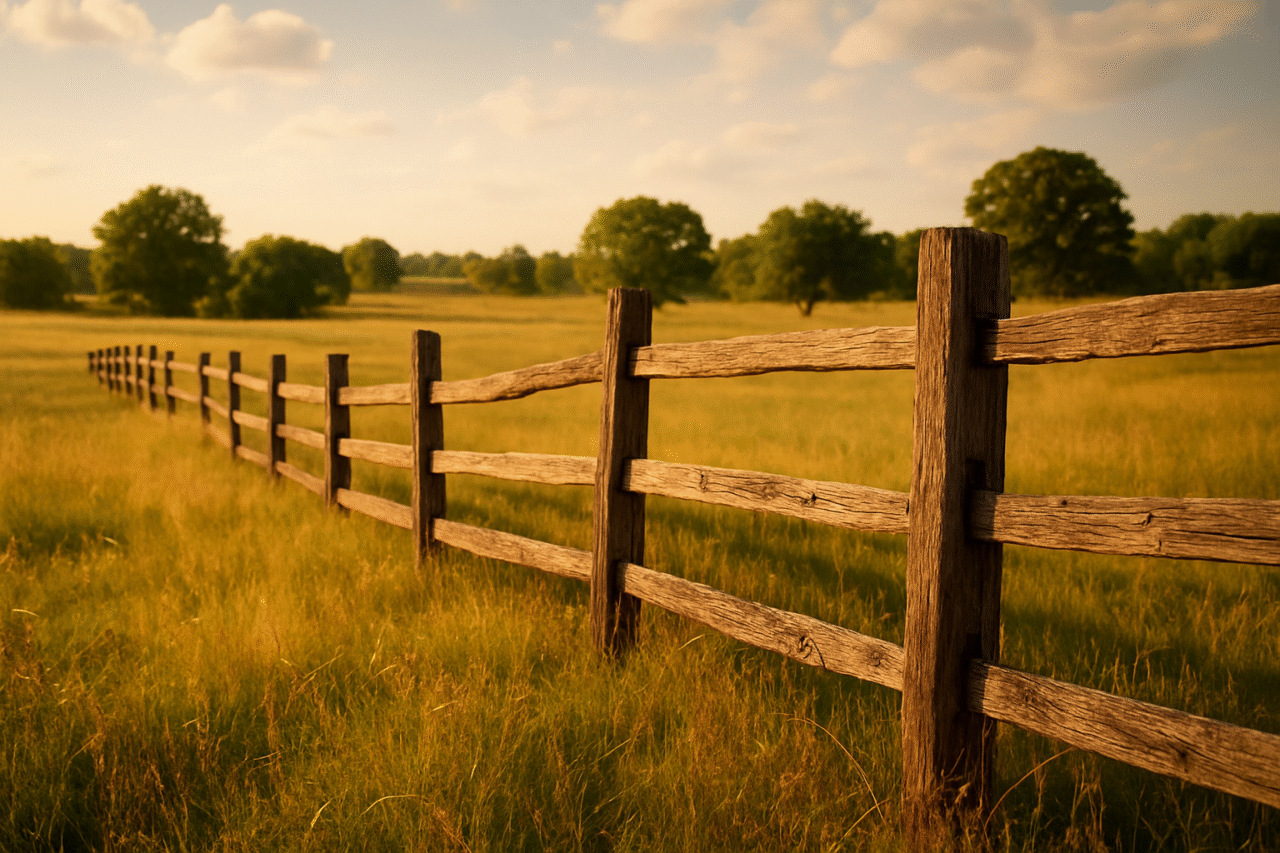

There exists… a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

So many of our ancient “institutions or laws”, as Chesterton refers to them, are being purposely destroyed. Gender roles. Cultural norms in appearance. Marriage. Capitalism. America. Free Speech. The Constitution. Parental consent. Religion. National borders. Even the definitions of words are being thrown away and sometimes replaced with the opposite meaning.

Many who live and benefit from these fences every day are actively fighting to obliterate them, or, at the very least, allowing them to be torn down without much of a fight.

I think it’s good to ask questions about our cultural norms and to consider change, but the more that I’ve sought to understand the value that our cultural fences have provided, the more that I’ve wanted to fight to preserve most of those fences.

The Fence Itself Proves its Value

The liberal will rightly point out the damage done by some of our cultural fences but will rarely even attempt to find the value that that fence provided. Another way of saying this is that, from a conservative’s perspective, liberals frequently throw the baby out with the bathwater without even looking to see if there was a baby at all.

But the very existence of the fence proves that there is (or once was) value.

In order to explain what I mean, let me paraphrase something that I learned in a book (A Hunter Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century) written by Bret Weinstein and Heather Hying, two evolutionary biologists and self-proclaimed liberals.

To my mind, they made a few earth-shattering claims, one of which is the idea that cultural traits are evolutionary. They are passed from generation to generation, they are shaped by the environment, and they, in turn, impact the genome.

In other words, many of those annoying, backwards, or even literally-wrong pieces of our culture have (or had) a purpose. They might be evolutionary adaptations that provide value. Maybe we shouldn’t be so cavalier about throwing them away.

Weinstein and Hying asserted a three-part test to determine if a trait (whether physical or cultural) within a given species is an adaptation. They wrote,

If a trait:

- is complex,

- has energetic or material costs, which vary between individuals, and

- has persistence over evolutionary time,

then it is presumed to be an adaptation.

So, is a cultural trait, like monogamy, an evolutionary adaptation?

Is it complex? Monogamy, as a concept, is pretty simple: one man and one woman, for life. But the function of a human, monogamous relationship and what it takes to make it work is very complex.

Is it expensive? Without question! Monogamy requires immense sacrifice and tradeoffs from all parties involved.

Has it persisted over time? Monogamy has been the standard in Western culture for thousands of years.

So, monogamy is an evolutionary adaptation — a cultural fence that should be carefully examined and understood before we consider any alternative, either at a macro or micro scale.

Some Fences Need to Be Torn Down

Just because a cultural trait is an evolutionary adaptation doesn’t mean that it should remain in-place forever. (Chesterton didn’t say, “never tear down fences”. Slavery, is also probably an evolutionary adaptation, but no one would argue that we shouldn’t have torn that fence down.) It just means that we should first understand the value that the fence provided before considering its destruction.

Fences Rarely Get Rebuilt

Once a fence is torn down, it is unlikely to be rebuilt. Those that are rebuilt are only done with a fight, and a heavy price that society is unlikely to pay unless things get desperate. So, consider carefully before you advocate tearing down something that has provided value to society for generations. If you don’t see the value, it doesn’t mean it has none. It means that you don’t understand it yet.

Conclusion

Much of the advice that I want to pass along stems from this principle: look to history and to your ancestors for wisdom. Don’t fall into the logical fallacy of believing humans of today are so much wiser than humans of the past. Though your time in history may be unique, your struggles are not. Follow the path of those who have gone before you and who have created successful lives. Disregard their path only with trepidation and careful consideration.

Don’t be like King Rehoboam:

4 “Your father put a heavy yoke on us, but now lighten the harsh labor and the heavy yoke he put on us, and we will serve you.”

5 Rehoboam answered, “Go away for three days and then come back to me.” So the people went away.

6 Then King Rehoboam consulted the elders who had served his father Solomon during his lifetime. “How would you advise me to answer these people?” he asked.

7 They replied, “If today you will be a servant to these people and serve them and give them a favorable answer, they will always be your servants.”

10 The young men who had grown up with him replied, “These people have said to you, ‘Your father put a heavy yoke on us, but make our yoke lighter.’ Now tell them, ‘My little finger is thicker than my father’s waist. 11 My father laid on you a heavy yoke; I will make it even heavier. My father scourged you with whips; I will scourge you with scorpions.’”

12 Three days later Jeroboam and all the people returned to Rehoboam, as the king had said, “Come back to me in three days.” 13 The king answered the people harshly. Rejecting the advice given him by the elders, 14 he followed the advice of the young men and said, “My father made your yoke heavy; I will make it even heavier. My father scourged you with whips; I will scourge you with scorpions.” 15 So the king did not listen to the people, for this turn of events was from the Lord, to fulfill the word the Lord had spoken to Jeroboam son of Nebat through Ahijah the Shilonite.

16 When all Israel saw that the king refused to listen to them, they answered the king:

“What share do we have in David,

what part in Jesse’s son?

To your tents, Israel!

Look after your own house, David!”